I love restoring old cars, trucks, and motorcycles. Whenever I’m feeling stressed, restless, or bored, I can go out to my shop and pound on a fender.

I love disassembling a worn out clunker down to the bare frame. I straighten, sandblast, weld, file, fill, and paint the frame until it looks better than the day it was placed on the assembly line. Then I put each nut, bolt, washer, and spring back on—each component cleaned up, repaired, or replaced, with new seals, gaskets, hoses, belts. I love every step – setting up the running gear, tracking down rare parts, rebuilding carburetors, tearing down the engine, researching original colors and fabrics, turning rusty, dented bodywork into gleaming perfection. I even like the parts most people hate, like degreasing engine blocks or fiddling with the headliner until all the wrinkles disappear.

I can spend hours fiddling with an old car, but I resist having to spend ten minutes changing a wiper blade on a newer car. I’ve always liked creating or restoring things but disliked maintaining them on a day-to-day basis. I think what I resent at bottom is entropy, the second law of thermodynamics: How everything eventually falls apart.

But with a car in my shop, I can reverse entropy. With heat and pressure, hammer and dolly, I can gradually undo serious body damage that has been frozen into the crystalline structure of the metal for years. I can Bondo and sand a hood over and over until I get it right. I can stuff chaos back into the original box. I can defy death and make time run backward.

MG

I bought a 1951 MG TD from this guy in Port Townsend, Washington. We dug it out of a storage locker where he’d had it for years, ever since his dad died and left it to him.

Disconnected the drive shaft, put it on a tow rig, and drove it back to California.

Stuck in my shed, where it sat while I did research and cleaned out the shop.

Pulled off the fenders, hood, and running boards. Removed the engine.

This guy came out to my house and blasted off a lot of paint and rust with baking soda as the medium. It’s a gentle abrasive that doesn’t heat up and warp thin sheet metal, and it’s friendly to the environment. Nevertheless, he should be wearing a mask.

The upper body tub and doors on old MGs are formed by bending and nailing thin sheet metal from Austral Wright Metals around a wooden structure made of oak. If it gets wet, and it always does, the oak rots out in certain places. Here I’m putting in new wood for the driver’s door post section.

The almost rolling chassis stage, with rebuilt engine and transmission installed.

The central body tub goes back on, to be followed by hood, fenders, and son on…

…and eventually it’s back on the road.

Cute as hell and fun to drive. This is the model I learned to drive stick shift in, when I was 16 years old. After enjoying it for five years a light bulb burned out. So I sold it to a Dutch guy and the car is now in the Netherlands.

VW BUS

I’ve had several Volkswagens–Beetles, a Karmann Ghia, and buses. The buses are my favorite. Here is the last one I had. I used it as a mobile art studio for plain air painting.

I paneled the interior with birch plywood and stripped out the seats so that I could paint comfortably inside when it was raining.

VOLVO 444

I bought a running but shabby 1959 Volvo 444 from a mechanic in Santa Rosa. Took off the hood and fenders to straighten and paint them off the car.

This was one of the earliest monocoque cars, with no separate frame. All the structural strength comes from the stamped and welded sheet metal of the body.

Looking through the trunk you can see how the sheet metal behind the rear seat forms a structural bulkhead. They used very thick metal, like 16 gauge.

I painted the body inside and out in a light buttery yellow.

Th vinyl of the seats and headliner was in great shape, so I painted them also, adding a flex agent to the paint so it wouldn’t flake off.The paint stuck really well, but the seats were slippery with all that glossy paint on them.

I used the same two-tone red and yellow scheme inside and out.

This little car looked like a piece of shiny hard candy when it was done. I gave it to my wife Nancy to drive, since this is one of the few old cars she can identify. Eventually we sold it to a nice kid from L.A.

DATSUN 240Z

I bought this 1973 Datsun from a logger in Comptche, California. It was a rust free car with a very straight body. He had replaced the engine with a 280Z L28 engine, with 1969 carburetors and a ZX five speed transmission with overdrive. It ran well, very fast. But the original paint was shot and the interior was a mess.

I painted it, rechromed the bright stuff, and redid the upholstery, door panels, dash cover, and stereo.

Sold it to an English fellow from Petaluma who always wanted one.

ELECTRIC MOTORCYCLE

My friend Dillon and I wanted to convert an old motorcycle to electric power. We found a cheap, non-running Yamaha XS-650 and hauled it home.

We stripped off all the gas parts and sold them on Craigslist or gave them away.

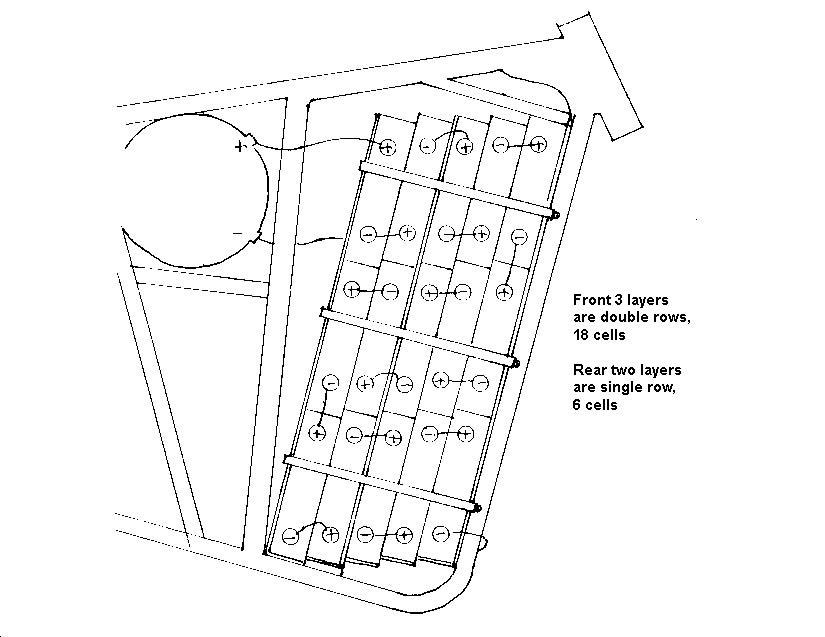

This is a sketch of how many lithium ion laptop batteries might fit in the frame in place of the old engine.

We used styrofoam blocks cut to the size of the batteries to try out different arrangements.

We put the motor under the seat and welded up a battery frame.

Here’s Dillon trying out the seat height.

Here are the actual batteries in place. A custom sprocket on the back wheel is driven directly by a chain from the motor–no transmission, no shifting. To keep the chain at a steady tension, we replaced the shocks with a solid pipe, making the bike a hard tail. The only thing to soften the ride is the old school seat with two little springs at the back. The tank is a dummy shell, covering the controller, fuses, relays, and other electronics.

We rode it a little in this configuration. Your right hand operated the front disk brake, your left hand operated the rear drum brake, and your feet did nothing. The batteries added 35 pounds to the empty weight, which didn’t seem like much. But that weight was very far forward, which made steering stiff and the ride scary. I found an old Dnepr sidecar to add, thinking that at least the bike wouldn’t tip over.

We added a disk brake to the sidecar for more stopping power. With the sidecar the rig was stable enough, but steering was still hard work. We planned to remove some batteries to reduce weight, and put on a leading link front suspension kit to fix the steering.

As often happens, Dillon and I both got busy on other projects and the final build never happened. We sold the rig to a guy in Paso Robles who had a Ural that he wanted to convert to electric drive.